We don’t need a degree in neuroscience to assume that maybe the brain and gut are somehow connected.

When we prepare to give a presentation, the feeling of “butterflies” in our stomach, stress-induced stomach ulcers, emotional eating, and even our intuition showing up in the form of a “gut feeling,” all provide some clues which lead us to believe that the brain and gut are connected.

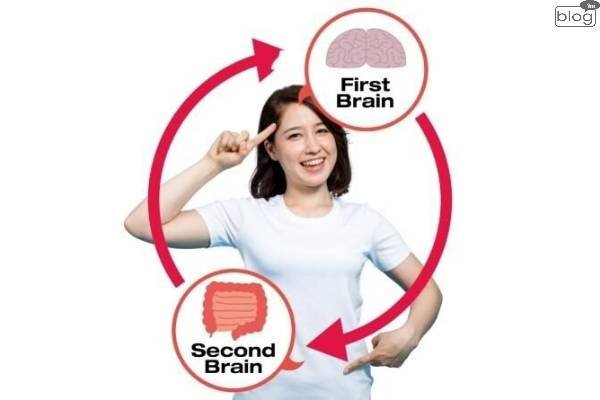

But what we do not know is just how connected the brain and gut are.

Emerging evidence from research is showing that the gut–brain axis is one of the most powerful relationships in our body.

It has earned the nickname “second brain” because it is composed of 100 million neurons, and the network of nerve cells lining the digestive tract is so extensive.

But technically it is known as the enteric nervous system and this network of neurons is often overlooked and contains more nerve cells than the spinal cord or peripheral nervous system.

Beyond the sheer volume of neurons, our second brain bears even more resemblance to the brain in our heads.

The mass of neural tissue in our gut produces over 30 different neurotransmitters, which are signaling molecules typically associated with the brain which also include a staggering 95% of the production and storage of serotonin, the neurotransmitter famously known as the “happy chemical” due to its role in regulating mood and wellbeing.

Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorder, etc. and so many neurological conditions are correlated with gastrointestinal issues or altered gut microbiomes.

Inflammation can be caused by the trigger of an immune response which happens due to disruption in the health of the gut microbiome.

Over 70% of the body’s immune cells are targeted to the digestive tract—which is helpful in the case of ingesting toxic bacteria—but also means a gut-immune response can launch a powerful inflammatory response in the body.

Reduce inflammation and stress have been detected by the stimulation of the vagus nerve.

And some researchers are also suggesting that vagus stimulation could be a new drug-free antidepressant.

Some certain healthy gut bugs such as the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus can even send signals to neurons to release GABA, a neurotransmitter that promotes calmness.

Neuroplasticity is also promoted by gut microbes which is a process implicated in the mood.

While it is now clear that the gut is more than just a machine for digesting food in our body.

But there is still much to be discovered in terms of how the gut can influence our overall health.

By the way, when our understanding of the gut–brain axis increases, there is the exciting possibility that improving gut health may lead us to breakthroughs for treating brain disorders.

To read more blogs,click here

Writer

Kulsuma Bahar Bethi

Content Writing Intern

YSSE