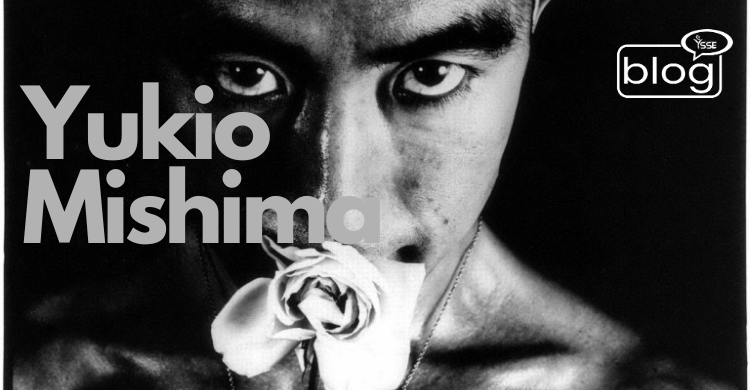

Yukio Mishima is now considered Japan’s most well-known author. He wrote 35 novels, 25 plays, 200 short stories, and eight collections of articles before his death. Everyone was particularly interested in his personal life and works of fiction.

Childhood Times

Kimitake Hiraoka was Mishima’s real given name. As he reflected on his childhood, he envisioned himself as a boy looking out a window, unable to affect the world around him, and hoping for it to change on its own. At seven weeks of age, his grandmother took him away from his parents. His grandmother, who was overprotective by nature, treated him like a delicate, frail plant.

Thus, rather than playing outside with other boys, he had spent years locked in her sickly-sweet-smelling bedroom.

The boy’s mind evolved in the room. Fantasy and reality have an unbreakable bond; fantasy, the more dominant sibling, gradually took over. After the death of his grandma, he developed an obsession with roleplaying. He viewed life as a performance. He can’t stop himself from placing fantasies in the real world.

His father, Azusa, preferred military discipline and was concerned that her (Mishima’s grandmother’s) parenting style was too gentle. One day, Azusa saw his son holding a lovely cat and petting it on his lap. This sight was deemed unmanly and annoying. So he threw it away.

School Life

Later that year, he entered middle school.

“All right, you cowards! Who’s next?” “Who is this? The poet? Mr. Tough?”

They bullied him. He was shaking. “You’ll get killed! Mama’s boy!”

In his early years, he realized the existence of two opposing factors. He saw:

The first is words, which can transform everything in the world.

The other element was the world itself, which had nothing in common with words.

For the average person, the body precedes language. In his case, words came first.

A Pen for Redemption

At the end of the war, Mishima felt left behind.

He believed he was meant to be the icon of his era. He thought himself to be a kamikaze for aesthetics. But he thought he had only been a boy who wrote bad poetry. He quit his job at the Ministry of Finance to become a writer. Confessions of a Mask was done only in 6 months. Then he finished Thirst for Love in 5. Forbidden Colors took 9, Sound of Waves 4, Modern Noh Dramas 3, and The Temple of the Golden Pavilion 10 months.

Mishima found inner peace in writing in the middle of his emotional turmoil. His pen became a weapon to defend his proud nation, an escape from the nightmares that tormented him.

The Quest for Beauty and Destruction

Mishima’s books have gained immense fame and reputation around the world, even though nearly all of his characters and settings are based in Japan. The stories explore a wide range of themes, from darkness to death, and the struggle to achieve beauty, spirituality, and transformation. He sought beauty—sublime, elegant, and divine. His writings span tradition and revolution, combining Samurai morals with modern ideas.

Sun & Steel

In 1952, Mishima visited Greece and discovered Greek sculpture. Greece cured his self-hatred and awoke a will to live. These sculptures inspired Mishima to begin bodybuilding. They made him realize that

“beauty and ethics are the same. Creating a beautiful work of art and becoming beautiful oneself are identical.”

Death

On November 25, 1970, Mishima and his private army kidnapped the commander at the Tokyo base, had him assemble the army battalion, and then tried to start a coup. He told them not to follow the US because the US has crippled the constitution and made the government into a puppet government, and he challenged them to reinstate the emperor as national leader.

The audience just stunned him into silence and soon drowned him out with boos. Mishima stepped back inside and said, “I don’t think they heard me.” Then he committed ‘Seppuku’, the Samurai’s ritual honorable death.

Mishima’s small life may be regarded as a life of patriotism, honor, and duty. He always strived for beauty and greatness in his day-to-day life. Mishima thought today’s generation never thought about the future. “They never think about the past, and they’re always jumping and jumping from moment to moment,” he said in one interview. “You see, well, do you think they’re going to find a purpose? I hope so, and it is also my problem.”

Mishima sent a message for us: “We live in an age in which there is no heroic death.” He preferred dying at a young age with purpose and full of honor to living a long life of regrets.

To read these types of blogs, please visit here.

Writer,

Sadi Reza

Intern, Content Writing Department

YSSE.